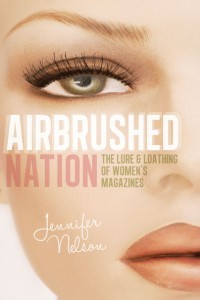

We’re sometimes-proud, sometimes-guilty junkies of women’s magazines, so we couldn’t wait to get our hands on Jennifer Nelson’s new book Airbrushed Nation, in which she givesGlamour, Cosmo, et. al. a critical once-over. We talked to Nelson about the good, the bad, the unrealistic, and the terrifying behind the glossies that rule so many women’s lives.

We’re sometimes-proud, sometimes-guilty junkies of women’s magazines, so we couldn’t wait to get our hands on Jennifer Nelson’s new book Airbrushed Nation, in which she givesGlamour, Cosmo, et. al. a critical once-over. We talked to Nelson about the good, the bad, the unrealistic, and the terrifying behind the glossies that rule so many women’s lives.

What’s the most surprising thing you learned about women’s magazines in researching this book?

I’d have to say what was most surprising was how I hadn’t even noticed that every topic was approached from a “women aren’t good enough as is” mantra. All the articles from relationship pieces to sex tips to dieting, beauty, aging, even health and money stories are approached as though women need to fix something about themselves, or everything about themselves. This is very different than how men’s magazines approach their stories. There, they think men are just glorious as they are, and they simply offer up articles to inspire, inform, provide humor, or entertain them. Women’s magazines call their books “service,” which is supposed to mean that the stories provide advice and a take away for everything you read, but service has really become another word for makeover.

Why is it so important to look at what women’s magazines are doing? Does anyone take them seriously anyway?

Well, yes actually, that’s the problem—women are taking them seriously apparently. Research has found that after one to three minutes of paging through a chick slick, women feel worse about themselves than they already did. And that three quarters of the cover lines on these magazines provide at least one message about altering your body via beauty products, dieting, exercise or cosmetic surgery. That’s a lot of negative messaging women absorb for simply

browsing through the silky pages. Young women and girls seem to be most affected but that’s where it starts—when we’re young. No matter which magazine you read from Seventeen to Good Housekeeping, typically thought of for older women, the message is the same, the mantra that we’re not good enough and that every photo needs to be airbrushed is drilled into our psyche from the teen years and beyond.

What’s the worst of the messages these magazines are putting out these days?

One of the biggies may be aging—or rather the lack of it. Every magazine from the twenty- something centric Cosmo to the over 40 focused More magazine spotlights the anti-aging movement. Magazines like More who run articles about empowering older woman no matter their age still stick an article on how to look younger, dress younger, act younger or apply makeup younger the very next page. What the hell, right? On the one hand, they tell us, embrace our chronological number and all that comes with it including crow’s feet and wisdom, and right next door they insist on sharing the best ways to act, look, appear and think younger. And almost worse, is that the twenty-something magazines like Cosmo, who’s readers show no visible signs of aging as of yet get an up close and personal look on how they should begin their anti-aging assault as well. These women are being hawked eye serums and wrinkle creams along with their mothers and every other beauty article is about anti-aging. It’s certainly both an advertising-driven paradigm as well as a cultural phenomenon that is wreaking havoc with women’s self esteem and beauty ideals.

You’ve written for tons of these magazines. What inspired you to write this? And were you afraid of never getting work again from them?

Ha! Yes, it is pretty much my exit out of writing for women’s magazines. But truth be told, I had already made the shift over the past couple of years. The year before I wrote the book, I had written exactly two pieces for them, and the year I wrote the book, none. The reasons were two-fold, one because as I began dissecting them more and more and realized what negative messaging they continue to perpetuate, I began to distant myself a bit from wanting to write those kinds of stories and contribute to that message. And secondly, the women’s magazines don’t have such a stellar reputation for being great places for writers to work. It can take months to get your ideas vetted and accepted, editing is often a long, drawn out process that can take months and involve several editors and a few rewrites and finally, getting the article approved and a check cut can take even longer. Writers sometimes wait from 6-12 months to finally get paid. It’s a somewhat difficult and arduous process fraught with obstacles.

What do you think is the genuinely best women’s mag for women, and why?

I don’t know if I can offer a “best” since that’s probably subjective but I can offer a few suggestions and why. A magazine like Real Simple, which still covers some fashion (albeit, mostly minus the airbrushed models) as well as traditional women’s magazine fodder like food, crafts, home décor and essays is a good example of a magazine getting it mostly right. It’s often missing the “you must improve yourself” mindset as well as the offending digitally manipulated

images, and so overall it gets top marks. Better Homes & Gardens may be a close second with a focus on the home and its surroundings with a few of the traditional lady topics thrown in. But women should ask themselves if paging through their favorite glossy makes them feel worse about themselves afterward, and if so, they might take a magazine sabbatical, or simply look for those magazines that may carry content of interest: food, décor, money, essays without so

much of the negative messaging and airbrushed ideals.

What’s the future of women’s mags? Will we ever get more variety and depth from them, or are we doomed to eye shadow and weight loss stories forever?

Well, first, I don’t think women’s magazines are ever going away. Despite recessionary periods, e-readers, and the fabulous proliferation of online magazines, women’s print glossies will remain. They’re iconic and each generation has embraced them similar to the way our mothers and grandmothers did. But I do think they will have to move toward more depth and less of the controversial coverage we see today. We are making small inroads. Girls petitioned Seventeen

magazine and met with their editor in chief asking them to stop airbrushing the teen girls in the pages—and the magazine complied. Glamour magazine also vowed this year to stop altering a woman’s body via Photoshop. These are huge improvements, but of course, there is still a lot of work to be done on the article content and the messaging that women aren’t good enough as they are. I think the only way we will get more depth from them is to demand it. Women need to consider that their subscription dollars and newsstand change make a difference. Buy into magazines you feel are getting it right and let those that aren’t know how you feel. Facebook them, Tweet them, send an email to the editor-in-chief. Social media is a powerful tool women have at their disposal. It’s only by the masses letting them know we want more than eye shadow and makeup tips or blatant sexist questions in every celebrity or woman politician interview that the magazines will know that we want more.

We had just been chastised to keep our voices down—this was, after all, a meditation retreat, and we were supposed to be in silence. But my roommates, two 60-something women named Joan and Linda, and I were amped up on late-night (in this context, that’s about 9 p.m.) girl talk. And I was about to receive the most profound insight I would all week, not from the six hours of meditation we did every day, nor from the spiritually rich talks the teachers would give. In fact, what my roommate, Joan, said next counts as one of the great insights of my life. “Jennifer, just wait until you get old,” she said. “Spending a thousand dollars on a Tempurpedic bed is no longer an indulgence, it’s a medical necessity. Getting old is the best!”

We had just been chastised to keep our voices down—this was, after all, a meditation retreat, and we were supposed to be in silence. But my roommates, two 60-something women named Joan and Linda, and I were amped up on late-night (in this context, that’s about 9 p.m.) girl talk. And I was about to receive the most profound insight I would all week, not from the six hours of meditation we did every day, nor from the spiritually rich talks the teachers would give. In fact, what my roommate, Joan, said next counts as one of the great insights of my life. “Jennifer, just wait until you get old,” she said. “Spending a thousand dollars on a Tempurpedic bed is no longer an indulgence, it’s a medical necessity. Getting old is the best!” With all the self-tanners on the market today, it’s hard to believe that women in the 18th and 19th centuries sought white, pale skin—the beauty ideal at the time. But just as we use product to make us look like we returned from a week in Cancun, Victorian women used primitive cosmetics to achieve their version of the perfect skin tone.

With all the self-tanners on the market today, it’s hard to believe that women in the 18th and 19th centuries sought white, pale skin—the beauty ideal at the time. But just as we use product to make us look like we returned from a week in Cancun, Victorian women used primitive cosmetics to achieve their version of the perfect skin tone. On my third date with Alexander, after he stripped me down to my underwear, I reached for the metal button on his jeans. Hard and out of breath, he blurted, “I don’t want to have sex.” My hand froze at his waist. “I mean, I don’t want to have sex yet,” he clarified.

On my third date with Alexander, after he stripped me down to my underwear, I reached for the metal button on his jeans. Hard and out of breath, he blurted, “I don’t want to have sex.” My hand froze at his waist. “I mean, I don’t want to have sex yet,” he clarified. The miscegenation of our society may seem to be growing at a steady rate based on how often we’ve been talking about race lately. But let’s not kid ourselves. Interracial relationships represent approximately seven percent of couples in the country, which is incredible progress considering they represented just .07 percent in 1960. But for our ever-diversifying nation, these are alarmingly low figures. For the most part, everyone is stillsticking to their “own kind.” Is this intentional segregation or just cultural tradition? Could be both. But one thing remains certain: Every interracial couple entering into a serious relationship knows what struggles lie ahead. Maybe that’s why 93 percent would just rather avoid them.

The miscegenation of our society may seem to be growing at a steady rate based on how often we’ve been talking about race lately. But let’s not kid ourselves. Interracial relationships represent approximately seven percent of couples in the country, which is incredible progress considering they represented just .07 percent in 1960. But for our ever-diversifying nation, these are alarmingly low figures. For the most part, everyone is stillsticking to their “own kind.” Is this intentional segregation or just cultural tradition? Could be both. But one thing remains certain: Every interracial couple entering into a serious relationship knows what struggles lie ahead. Maybe that’s why 93 percent would just rather avoid them. Wanna save an extra $5,000 a year? Become a man!Seriously, I could be rich (or at least get richer faster) if I gave up my beauty routine. Currently, my daily self-prepping involves the following: shampoo, conditioner, shower gel, face wash, toothpaste, body lotion, face moisturizer, blusher, a bit of glimmer for my cheeks, eyeliner, mascara, lip gloss, and perfume. And I’m a basics kind of gal. Most American women also add in regular salon and spa stuff like spray tanning, waxing, highlights, haircuts, manis, pedis, microdermabrasion and Botox.

Wanna save an extra $5,000 a year? Become a man!Seriously, I could be rich (or at least get richer faster) if I gave up my beauty routine. Currently, my daily self-prepping involves the following: shampoo, conditioner, shower gel, face wash, toothpaste, body lotion, face moisturizer, blusher, a bit of glimmer for my cheeks, eyeliner, mascara, lip gloss, and perfume. And I’m a basics kind of gal. Most American women also add in regular salon and spa stuff like spray tanning, waxing, highlights, haircuts, manis, pedis, microdermabrasion and Botox.